In dreams, I am the emperor of ice: a thousand white

wolves galloping through wave after wave of snowfall,

its shards like diamonds the size of dice. The dogs

are without names in this vision; almost imperceptible

against the silver landscape, but I call to them now, one

by one to fill the dark, my feet scaling mountains

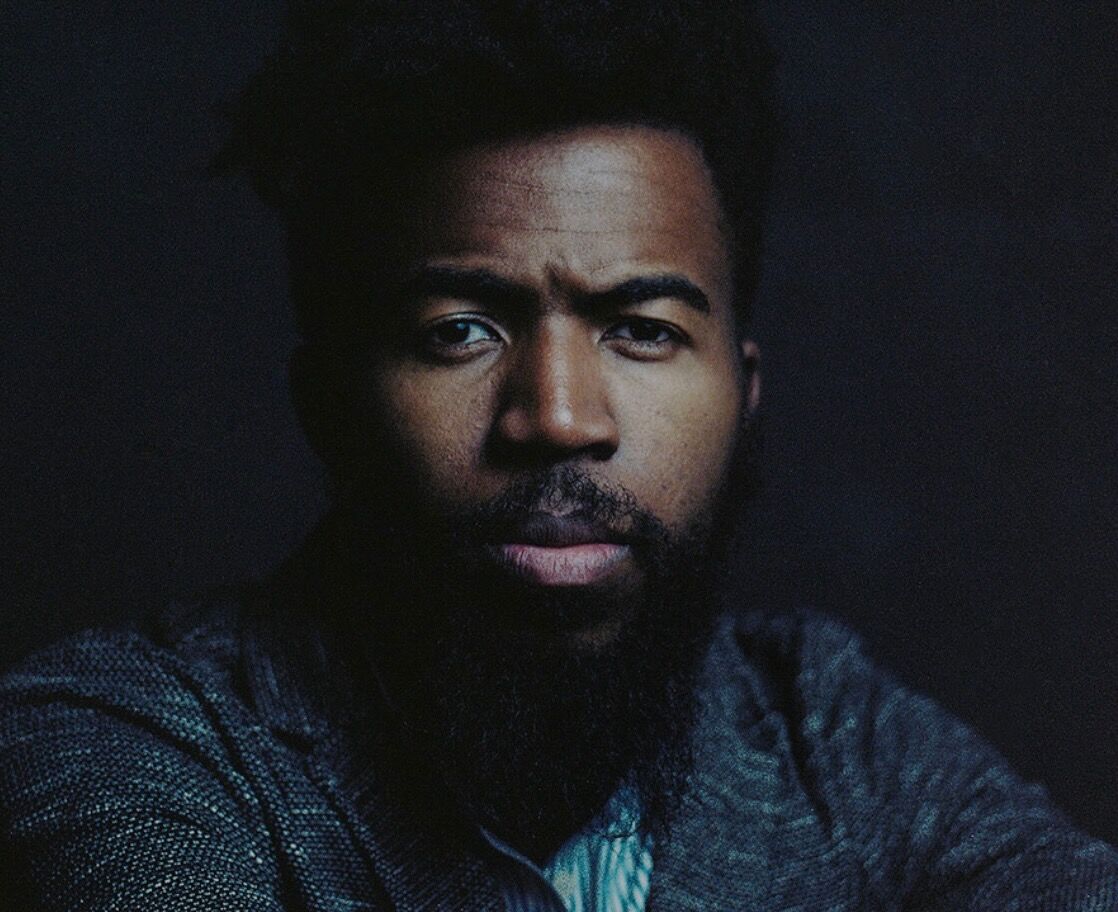

without touching them. Ascending, I see Matthew Henson,

who once cut a figure in church calendars and hardback

children’s books like no other, powder-flecked fur a halo

around his face. Unsmiling always; stalwart; an explorer

beyond the need for language or backstory, it seemed,

as if he had emerged in totality from some floe in the middle

of Antarctica, the first black man to hold the North Pole

in his glare, designed for the glory and dangers of life

below zero. The second was Herbert Frisby: biologist,

educator, Alaskan correspondent for the Baltimore

Afro-American, tracking meticulously all that called

to him from within the polar vastness.

It was Frisby who fought for years to see Henson credited

with discovering the North Pole in 1909, back when he

was still a college student at Howard, living in the lab, yet

to make his twenty-six trips to the Arctic, fly over the apex

of the known world, meet the President, chronicle atomic

testing on Amchitka Island, teach children for decades

to cast their looking toward the unseen, whether microscopic, or

blanketed by winter, or obscured from the record until one dares

to inscribe the names of our champions into the grand American

Mythos with exactitude and grace, and thus catalog their footprints

in the mud, and the grass, and the snow of History, refusing to

relinquish what we are everywhere assailed for remembering.